Individuation

There are restless spirits in our psyche

longing for, or demanding,

embodiment.

JUNG NAMED the process of incarnating a greater, more coherent and distinctive personality “individuation.” Individuation is a lifelong process of growth and ripening. Jung observed that we, who are ordinarily loose collections of disparate and largely unconscious parts, have the capacity and the drive to become more integrated, more whole. The instinct towards wholeness is innate but to be aware and active in the process is a blessing, a crown of human experience.

Psyche seeks balance, not perfection.

Governed by a principle of self-regulation and a natural tendency towards healing, the psyche will do whatever it can to right a lop-sided attitude or lifestyle. Psyche seeks balance, not perfection, and accepting more of who we are is a marker of psychological maturity. While all human life moves towards wholeness, analysis can quicken the process, and help move us through obstacles or discouragement. Analysis helps to shine a light into the recesses of the unconscious and invite what has been hidden and neglected into the open.

THE SELF

The impulse to individuate belongs to the archetype known as the Self. The Self is an inner principle of order and orientation, active in the project of becoming whole. Like all archetypes, it expresses itself differently in each person, but it has the quality of a supreme value or transpersonal power. The Self will ultimately eclipse our small, egoic preoccupations and become the illuminating centre of a new personality.

INDIVISIBILITY & ETHICS

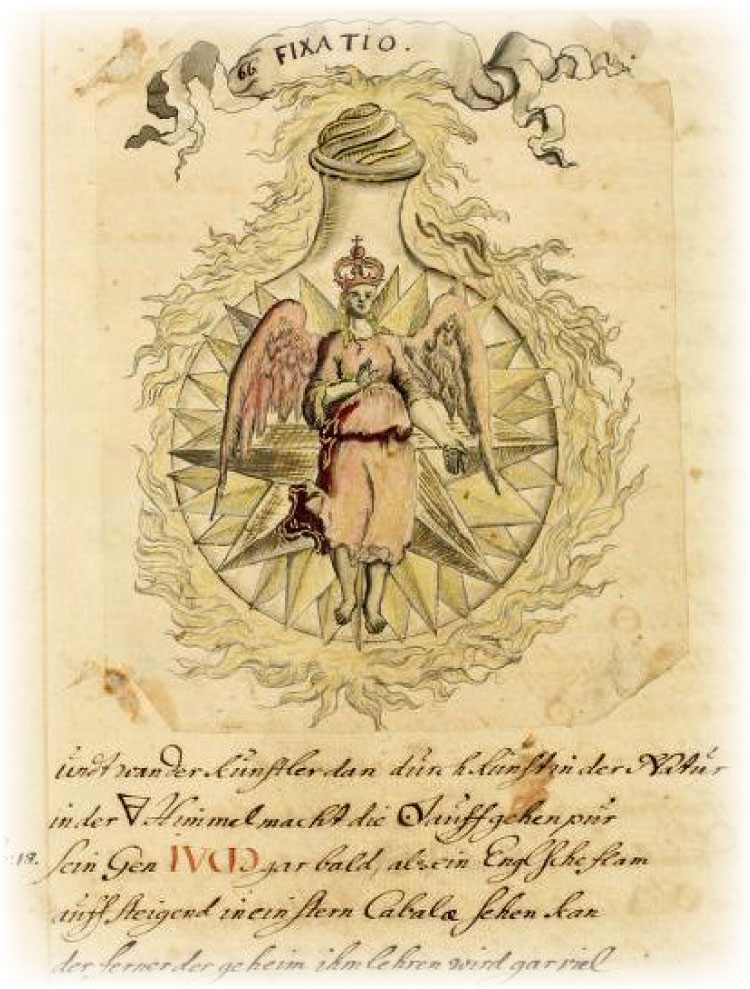

Individuation means becoming indivisible, without inner conflict. Jung made much of the parallel between the extraction of alchemical gold from lead, and the arduous process of making something incorruptible from the rough stuff of our lives. It is certainly a challenge to hold with equanimity our many contrary internal elements. We eventually learn to accept all that we are – not suppress, not judge, and not be blindsided or seduced by an urge that is harmful to ourselves or others. In balancing compassion and responsibility, an ego grounded in its own nature becomes an important gauge for discerning and choosing ethical behaviour.

SHADOW & PROJECTION

Usually we suppress aspects of ourselves that threaten, or conflict with, our idea of who we are. Ironically, these are the very qualities that irk or fascinate us about other people, for we neatly cut them out of our self-image and project them onto others. The total of these unowned or unknown aspects of ourselves is what is called shadow.

Projection is an automatic, unconscious function originating in shadow. We blame others for the very things we cannot see in ourselves, leading to a host of real-life problems. Yet, at the same time projection offers a reliable method of getting to know who we are. Stopping to challenge our judgments allows us to reclaim what the other is mirroring. Recollecting these split-off pieces is a large part of the work of becoming whole. Individuation requires that we rehabilitate and give place to these wandering parts of ourselves. Needless to say, our outer relationships benefit from the depth of honesty and acceptance that we can manifest.

INDIVIDUAL & COLLECTIVE

Jung saw personal individuation as the key to the evolution of humanity. “Only a change in the attitude of the individual,” he said, “can initiate a change in the psychology of a nation.”

As we individuate, we differentiate ourselves from the collective, extracting our particular qualities from all that we share with all humanity. We come to respect and trust our uniqueness. Yet we are not separated from the collective. Respect and trust in the uniqueness of others is a natural corollary of our learning. An individuating person is deeply committed to tending the suffering of the world.

Nor is this a selfish quest for purely individual salvation,

for just as the branches of forest trees intermingle,

so do their roots. . .

roots which interpenetrate with those of others.

J Layard

MID-LIFE & LATER CHALLENGES

In the first stages of life it is important to grow our ability to adapt and contribute to the world. Often it is in middle life that the first inklings of discontent, or the impossibility of clinging to a status quo, become apparent. Tried, and formerly reliable, ways of being wear out. Pressure from internal or external sources mounts, and propels us towards an ill-defined “something else.”

A potential danger we face when taking up the challenge to live beyond our known selves is projecting a cultural ideal as a goal. All too often, living within the confines of an ideal is what has created the impasse in the first place. So prescriptions about values or how to live that come from outside ourselves are not useful. It is our own nature we seek, not ideas about it.

On the other hand, stepping away from traditionally value systems, such as were once provided by religious institutions, produces anxiety. We suffer our alienation from safe cultural norms. Many sources of meaningful spiritual sustenance within our own culture have dried up. There are scarce gods to negotiate with or propitiate to bring us into balance. Being “modern” we delude ourselves that all healing is within our control. Rebuilding connection to the living psyche, tracking its archetypal imprint through dreams and communicating with it through imagination, restores a vanished or broken attitude of reverence. This too is a mark of individuation.

The dream leads in the end to that distant goal which may perhaps have been the first urge to life:

the complete actualization of the whole human being,

that is, individuation.

CG Jung

DREAMS

Dreams are key to the individuating project, as they are direct messengers from the unconscious. Individuation entails opening and maintaining channels of communication between our conscious and unconscious selves. Ego consciousness is what we develop to cope with the demands of life; but there are other distinct personalities within us that are not under ego’s control. They operate unconsciously, and powerfully, generating sometimes intense emotion. These complexes become more and more insistent on consideration as we age. Like independent personalities, they needle and niggle at us in ever more annoying and drastic ways. They are like restless spirits longing for embodiment or demanding attention. They show up as the players in our dreams.

Active imagination is most meaningfully defined as a dialogue with the gods.

Janet O. Dallett

ACTIVE IMAGINATION

Jung recommended this method to his patients in later stages of analysis, or when, as he said, there was no analyst available “under the changing moon except the one that is in your own heart.” It means that we observe and engage with the stream of our interior images by creative means. Dance, poetry, dramatic script, sand play, collage, painting, sculpting are all possibilities for capturing and elaborating the exchanges. To fully enter the experience, we must hold our disbelief at bay and allow ourselves to be swept into relationship with the unknown. And at the same time we must keep our discerning and evaluating capacities alert and active. This practice ensures that our conscious and unconscious sides forever walk hand in hand.

TIME

Engaging with the deep psyche requires humility and patience. Cycles of time and laws of nature beyond human measure or influence are at work in the unfolding of personality. Staying connected to dreams can keep us attuned to the movements of the Self, even if we do not fully understand them. The purpose of dreaming is to hold our attention on the deep processes at work in the psyche and hint at how we might align ourselves with them.

Individuation is a life-long process to which analysis contributes insight and impetus. It cannot be forced or halted, but it can be tended and appreciated. We are constantly oscillating between grace-filled moments of harmony and painful periods of discordance. This is the natural pattern of all growth and learning: a gradual, serpentine spiral.

Satori or individuation is the whole objective of our work.

It does not matter whether it is reached in this life or the next.

It is bound to guarantee peace;

otherwise what we are taught by the great religions is worthless.

Jane Hollister Wheelwright

Alison Vida

Salt Spring Island, BC Canada

alison@alisonvida.com