Dreams

It is a bird of the night.

It flies into morning

bearing a sign

from a distant land.

It seeks to guide

or prod

or orient us

to the real life that is ours.

av

THE DEPTH PSYCHOLOGY of Freud and Jung is founded on the premise that consciousness – what we are aware of – is only part of who we are. The smaller part. Freud and Jung mapped the unconscious from their distinct perspectives, declaring it an active partner in all that we think and do. Jung called the portion we can potentially access Shadow to indicate that it is shrouded in darkness. Once a truth submits to the light of consciousness and we know it, it is no longer properly Shadow. Beyond the personal shadow lies the collective unconscious, containing elements common to all humanity.

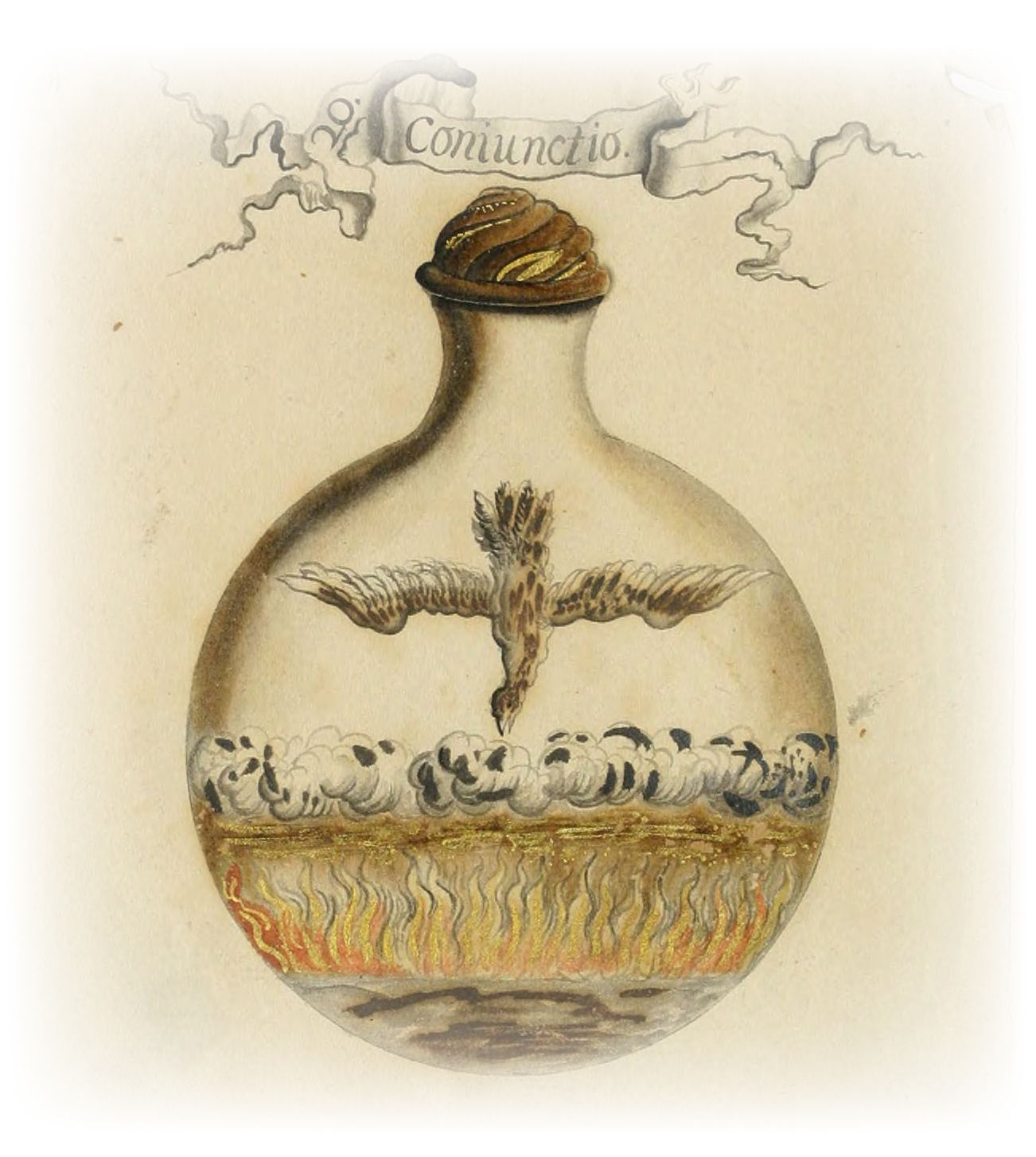

The particulars of the unconscious, being unconscious, do not lend themselves easily to scrutiny. The chief means available to us is to relate to our dreams. Dreams belong to an intermediary realm where elements of shadow rise to meet consciousness. They are a direct link to that vast, dark, mucky and fertile terrain in which we are rooted.

Jung’s thesis is that there is intention associated with dreaming weighted in the direction of growth and healing. Dreams are emissaries of the unconscious, and as such, they tell us something previously unknown and important. Dreams are the complement of conscious life in every conceivable way.

In each of us there is another whom we do not know.

He speaks to us in dreams

and tells us how differently he sees us from the way we see ourselves.

CG Jung

It is helpful to see the dream as a communication, not just an entertainment or idle fantasy. It wants us to understand something new. It brings information, generally specific to the dreamer, that stems from a variety of sources: physiology, genealogy, history, current affairs. Its message can be spiritual, relational, practical or prophetic. Like fairy tales, dreams speak a language of image, humour and intrigue. Often the content is cryptic, the meaning hidden or disguised, like that of a riddle or parable.

Every dream is a cipher, a little bead to worry in our hand, to muse over and ponder. Every dreamer has their own vocabulary within the languages of dream, which are rooted, like all language, in the pre-dawn of history. Getting to know our personal dream lexicon is a wonderful way to establish relationship with the larger part of ourselves.

It may seem counterproductive that dreams, so important to depth psychologists, do not just deliver their message in a matter-of-fact way. But “matter-of-fact” belongs to the daytime, rational, solar world. Nighttime, the other, lunar realm of the unconscious and dreaming is different. It is multilayered and fractal-like’ expanding the limitations of physical perception, of ordinary time, and certainly of ordinary logic. Jung called dreams “flimsy, evasive, unreliable, vague and uncertain.” This does not exactly inspire confidence in our fact-loving egos. The task of becoming whole requires that we develop ways of knowing that may be underplayed or undervalued. But because they require some mental and emotional effort to understand, we are more apt to take them seriously.

What informs my work, and what generations and cultures of dreamers have found to be true, is that dreams are psyche’s way of teaching and growing us. Ego needs to be challenged in this way. Dreams are always somewhat beyond our grasp, says Jung again. Yet, once unpacked, we find that they bring a purposeful, orienting message to the dreamer.

To discern that message requires us to grapple with all the elements of the dream. Meaning may come as a flash of revelation or take years of slow unpicking. But meaning there is. And if you think you know what that is on waking, think again. According to Marie-Louise von Franz, the unconscious does not waste much spit telling you something you already know.

A dream knows something you don’t.

Dream images are often shocking. Sometimes the shock factor wakes up to something that is right under our nose. Conversely, when they seem banal, we need to look further beneath the surface. Even when we think we have already learned some lesson or other, the dream may be warning us not to be too sure. It is wise not to take anything for granted when dealing with psyche.

As Jung suggests, we can neither dismiss dreams nor take them at face value. We may need to use our creative and intuitive and emotional intelligence to pierce their meaning. And in the interest of growing ourselves, we must do more than understand. We must relate to them and use our daytime skills to evaluate, counter, modify or fully accept what they say. Dreams – like symptoms – carry an ethical imperative. We are meant to do something with them. It is how consciousness develops. Book learning can make our minds grow sharp, while processing material from the unconscious enlarges consciousness itself.

The dream becomes a little hidden door

in the innermost and secret recesses of the soul,

opening into that cosmic night

which was psyche

long before there was any ego-consciousness . . .

CG Jung

Alison Vida

Salt Spring Island, BC Canada

alison@alisonvida.com